I’m an enthusiast. When something catches my attention, and particularly when it makes me happy, I like to share. I’ll be writing reviews fairly regularly, and mostly they’ll be of things that make me enthusiastic. So consider yourself warned. My reviews will come in two flavors: my reactions to reading and discussing a game, and my reactions to playing it. I hear there are gamers who fully grok the essence of a game just by reading it, but I’m not one of them; play always surprises me one way or another.

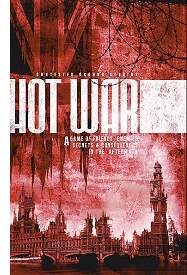

With all of that in mind, here’s my first reading review. Hot War is the new release from talented and fairly prolific British RPG writer Malcolm Craig. It is kind of sort of a sequel to his earlier game, Cold City. That’s set in 1950, with characters belonging to a multinational task force cleaning up the secret legacies of Nazi research: super-science, occult monsters, all the weird stuff. The heart of Cold City is trust and betrayal, with elegant, simple rules that make trusting and betraying both useful tactics. In the Le Carre-esque looking-glass world of conflicting agendas, it’s pretty well guaranteed that everyone will end up backstabbing each other over the good loot.

That’s where Hot War comes in. Now it’s 1963, and sure enough, the dangerous things didn’t stay locked up. The Cuban missile crisis escalated into nuclear war, and worse. The powers used gate-opening missiles and bombs on each other, launched troop carriers filled with ghouls and vampires, sent cybernetic zombies to spread diseases, and so forth and so on. A year after the brief war ended, the horrors continue. Hot War focuses on London and environs, a relatively safe stronghold in the midst of the chaos, with characters belonging to the hybrid Special Situations Group that pools police, military, and civilian efforts to promote public safety and order. Mechanically, the focus expands from betrayal to the whole spectrum of positive and negative relationships.

This is an absolutely marvelous game that fills me with envy, and I’ll go into detail below the fold.

By the way, I’m experimenting with the use of bolding to identify key terms and people, in these long pieces. I welcome feedback on that as well as the content of the review.

[More below the fold…]

The Book

Hot War is available from Indie Press Revolution, one of the best game storefronts on the net. Like most IPR releases, you can buy it in print, PDF, or both. The physical volume is 5.5×8.5″ – a typical digest format for rolegaming – but I have the PDF, compliments of the author. (Fair notice: I like Malcolm’s work and we have a friendly correspondence going. I am not a detached observer, though I try to be an honest one.) The PDF download is 20.9 Mb on my MacBook and comes with full-graphics and stripped-down, printer-friendly versions, plus the cover as a separate file. In either format, the book runs to 204 pages, which makes it large but not unusually so for a creator-owned RPG these days.

Malcolm consistently calls attention to the fact that it’s not his game alone. Paul Bourne delivers staggeringly excellent illustration and graphic design. Rather than me flailing away at description (though I’ll do some of that), I strongly recommend going to Malcolm’s business pages and downloading the preview PDF to see for yourself. I think the book looks better than most of my writing published by relatively large companies like White Wolf, frankly. The weathered page backgrounds suggest someone’s private record or copy of official documents that’ve taken a beating in the field. Digitally manipulated photos offer glimpses of the monsters, ruined landmarks, the victims of military justice, and other scenes of life in a cold and dangerous time. Propaganda posters pass along government and private messages on subjects from safely cooking rats to rallying against fear and in favor of a new fascist administration. It’s thoroughly evocative.

Preparing to Play

“Evocative” is a word I keep using for Malcolm’s writing, too. He’s as good as anyone I can think of now writing rolegames at suggesting a great deal while leaving as many details as possible open for individual groups of players to settle for their own campaigns. Thus there is, for instance, no detailed timeline of the war. There are documents presenting various views of the war’s first few days and slices of life month by month afterward to the game’s present moment. None must be presumed authoritative, and in fact one jumping-off point for campaign setup would be taking one of those documents and/or its author and letting the characters find out just how it’s wrong and right.

One of the ways the cumulative experience of rolegame creation and play shows is our collective tendency to write much clearer advice about setting up and playing the games than used to be the case. Malcolm does this as well as anyone I can think of, with a chapter that clearly spells out the distinct roles for players, their characters, the GM (gamemaster, or referee), and the NPCs (non-player characters) who fill the world around the protagonists. The emphasis is on cooperation in the real world to produce the most interesting conflicts and challenges in the game world. This happens to be a hobby horse of mine, and I’m always glad to see it addressed. Malcolm lists some possible overall tones and the kinds of story each involves, contrasting the quiet but intense character drama of the “Quality BBC Drama” style, the morally anchored action/adventure possibilities of “Post-Apocalypse”, the personal focus and willingness to take the larger background as given in “British Catastrophe”, and so on. He also reviews the potential strengths and weaknesses of “open” games, in which players know the secret agendas of the others’ characters, and “closed” games, in which only the player and the GM know each one’s secrets. He doesn’t rig it to promote whichever choice he may favor – it reads like he enjoys both, and wants to help his customers figure out what will actually be enjoyable for them for a particular campaign.

The Protagonists

With all of these things in mind, before numbers start getting crunched, Hot War asks one of the most crucial questions of all: What are characters doing? Discussion of possibilities, with good examples, follows, along with thoughts about antagonists and bystanders. Then there’s a neat section approaching a familiar topic – what sorts of scenes would we like to see? – in a distinctive and thematically appropriate way. Hot War encourages players to describe potential scenes with each captured in a single black-and-white photograph. Examples include “The photograph shows a manhole cover with blood pooling around it. The characters are all in the shot, their faces in shadow so it is hard to tell who is who. It is obviously dark and the only light comes from a hand-held lamp.” and “The photograph shows a street scene in front of a row of terraced houses. A young woman is pushing a rusty pram in the foreground. The front window of one house is absolutely filled with faces pressed against the glass, screaming in terror. The passers-by are oblivious.” This is the sort of thing that makes other game designers weep and swipe; it lends itself to vivid, focused, and evocative rather than constraining setups for later use.

Most small-press rolegames these days quantify characters’ abilities in broad categories rather than aiming for long detailed lists. Hot War takes this approach. Every character’s rated in three standard attributes: Action, which measures competence at physical actions, Influence, their degree of social leverage and skill at working it, and Insight, which covers mental clarity and stability, problem-solving skills, and other intellectual qualities. These are rated on a 1-5 scale, where 1 is just about barely there and 5 is the best you’re going to find in the course of the campaign; characters will have 3s and 4s in the traits that matter to them, 1s and 2s in others, by and large.

In addition, characters each have individualized positive and negative traits, institutional and personal hidden agendas, and positive and negative relationships with other characters and NPCs. Each of these warrants some separate discussion. When Hot War players want their characters to try something important, they roll dice, one die per point in the relevant trait – Action for physical conflicts, Influence for social, Insight for mental – plus or minus some dice for extra considerations. Positive traits add dice, and negative ones subtract them. Hidden agendas add dice if they enhance a character’s motivation in a particular conflict. Relationships add or subtract dice depending on their details. Okay, that sounds a little abstract. So…

Malcolm provides lists of sample traits for a dozen or so different kinds of common background. Here, for instance, are suggestions for characters who’ve been in the bureaucracy of any large institution, with + marking positive traits and – marking negative ones:

- Does everything by the book (-)

- Extremely bureaucratic and officious (-)

- Obsession with small details (+)

- Paragraph, clause, section, I know them all (+)

- Susceptible to charm and persuasion (-)

- Works very well under extreme pressure (+)

None of these are mandatory, and in fact the discussion around the examples explicitly encourages players to invent their own character-specific traits with the examples as inspirations rather than boundaries. However, using these examples as, er, examples…a character with these traits in a conflict of an unexpected sort that calls for innovation on the spot would lose an otherwise available die from her pool of dice to roll because of the psychological limitations in “Does everything by the book.” But if she and her allies in the Special Situations Groups were trying to make sense of a maze of calculated deceptions put forth by a sinister conspiracy covering its tracks, she might well get a bonus because of her obsession with details, her knowledge of the minutiae of regulations, or both.

A Note About Usage

I’m a big believer in inclusive language. I thought it was a good idea with somewhat tepid enthusiasm until I started writing regularly for White Wolf and ran into a whole lot of women wanting to thank authors for making them feel as welcome and expected as male players. Works for me. Malcolm handles the matter smoothly. The example players and example characters are both about half male, half female. When the GM is referred to outside examples, it’s as “she”; when the GM of the example group appears in play, he’s Stephen and gets the same treatment as everyone else. Hot War makes it easy to assume that women and men will both want to play and are welcome to do so. This makes me happy.

There was a very great deal of extended argument in newsgroups and web forums about this kind of thing back in the ’90s. These days it attracts much less attention. Many creators take inclusiveness as something almost as automatic as good grammar in general. Some want to make an issue of it, and do in little declarations about how “he” is inclusive it is it is too stamp my feet, and they get mocked by reviewers like me, and then we all get on with our lives.

(When I chatted with Mom this morning, I told her about the fun I was having writing this review, and mentioned touching on this topic. She laughed and remembered when inclusive usage first started attracting public attention. In the education field, some scholars wrote papers that simply used “she” as the generic third-person pronoun. Some readers, she remembered, vehemently protested that “she” cut out half the population, no matter what the writer might say. Then, she said, she was once again to have friends who taught her bits of Yiddish, because “Nu?” was the obviously correct response. But I digress.)

Back to the Protagonists

Cold War was Malcolm’s first stab at the espionage genre’s emphasis on conflicting agendas as important drivers of drama. He’s been thinking about it since then, and listening to comments from readers and players, and has added nuances to the subject this time around. Each character has an agenda inherited from their sponsor, like a Royal Navy member of the Special Situations Group charged to find evidence that can be used to argue for weakening the Army’s influence over SSG affairs, or a researcher assigned to identify and capture specimens of the various monsters afflicting the area the characters operate in. Each also has a personal agenda, like getting the love of their life to marry them, earning the respect of a superior who doesn’t appreciate them, or extracting revenge for the harm done to a family member by the authorities.

Having such things matter in game mechanics isn’t new, but Malcolm’s particular treatment is. Each character’s institutional and personal agendas are rated with a score of 3, 5, or 9. That’s the number of times the player can draw on it before it has to be resolved, and replaced by a new agenda of the appropriate sort. The clever part is that 3-rated agendas add 4 dice each time they’re used, 5-rated ones add 3 dice, and 9-rated ones add 2. Since 4 dice in an attribute means being well above average, those short-run agendas burn very brightly, just not for very long. I’m tempted to say “in true British fashion, no fire can blaze so hotly for very long”, but British friends would just fly over and curb-stomp me, so I won’t. But it does reflect a phenomenon in several of the subgenres that inspired this game: intense passions do burn out, while less intense ones can sustain a person through more thick and thin. Resolution of an agenda happens in a special scene of its own. The character sheet for the game (included in the preview PDF, linked to way up there early in this ramble) has spaces in which to check off the outcome of each invocation of the agenda, and the positive and negative legacies come into play in helping to determine whether the character got what they were aiming for, and at what cost.

Relationships are, like traits, rated + or – to describe the overall tenor of the relationship as far as the character’s concerned. There’s room for interpretation, too. An unrequited love might be positive if it draws the character on with some chance of success, inspiration to good deeds, and so on. It could also be negative, sucking away energy into a doomed cause and blinding the character to important aspects of the environment. Of such distinctions is fun character interaction made.

Finally, each player gets to describe a scene – in that style where it’s evoked via a single photograph – that they’d like to participate in. These complement the characters’ various scores and descriptions in helping the GM know what players want to get involved with, so that the GM can prepare appropriately.

Making It Go

The basic unit of action in Hot War, as in a lot of games these days, is the conflict. I’ve got a post simmering about levels of detail in resolving challenges, but I think this is long enough as it is; that’ll go up later. What matters to this particular game is that the dice come out once players have cooperatively framed the location – time, place, potentially involved NPCs, triggering events, and so on – and the nature of the conflict arising out of the scene. Not every scene has to have a major conflict, of course: sometimes characters travel from here to there successfully and observe things along the way, or search for something lost and find it, or make a briefing about crucial developments to an audience that listens appreciatively and understands the implications, and so on. All of this can be a lot of fun to play out, and if no conflict is called for, no dice get rolled. The players and GM reach for the dice when there is a conflict between participants in a scene, and something significant is at stake in their success or failure.

To take examples from the book….two characters disagreeing about just which weapons to take on patrol is not a conflict that calls for the game rules and dice, but the same two characters arguing whether to take a captured deserter back with them for study (he might be infected by one of the bioweapons, and if he’s still alive, the boffins will want to take a poke) or execute him on the spot (it’s the law) is significant.

The conflict is either primarily mental, primarily physical, or primarily social. That nature determines which attribute applies, and therefore how many dice each participant starts with – one per point in the attribute for that type of conflict. Then comes some time in which the players controlling each participant look to see what agendas, traits, and relationship may come into play. Malcolm encourages doing this cooperatively, with players free to suggest things like “hey, I think this may remind your guy of that time at Battersea, and could let you bring in that drive for revenge”. Players usually have the final say over their respective characters, and the GM resolves any lingering disagreements. At the end of this, each participant has a handful of ten-sided dice.

Everybody rolls. Whoever has more numbers higher than the others wins. Borrowing again from the book, if one player rolls 2, 2, 3, 4, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 9 and the other rolls 1, 2, 2, 4, 4, then the first has 5 dice higher than the second. (9, 9, 8, 7, and 6 are all higher than the 4 that’s the best result the second player got.) Each success lets the winner of the conflict assign a point of consequences. (There are some additional rules for multi-way conflicts, but all I need to do here is note that I tried them out with the sample and found them easy to follow and generating plausible outcomes.) Consequences range from single-point options affecting a single aspect of one of the participants, like turning a negative relationship positive (or vice versa) or improving a trait’s rating by 1 die, through to major changes each requiring several points of consequences to be assigned them, like reducing the score of one of the three traits for one of the participants down to zero, which puts them in catastrophic risk of ultimately dying, going mad, or otherwise shuffling off the stage as a protagonist.

Whether the consequences assigned by the winner to each participant are positive or negative depends very much on who won and who lost. What the rules do is standardize the availability of particular kinds of results, so that “did so”/”did not” loops can’t get started, and by listing a wide range of options, encourage the player of the winning participant to be creative in choosing the targets for each point of good or bad news and in suggesting what it is. And here again there’s room for cooperation, with the GM having the final say.

The player of the winning character also gets to narrate the outcome of the conflict, within some limits. No player can tell other players what their characters are feeling, for instance, though the narrator can set up something significant, awful, or otherwise engaging and ask what the other character feels about it. Players can’t tell the GM that their characters open the locked valise to find the particular atomic energy formulas they were seeking, but can say the valise spills open to reveal many interesting-looking documents and let the GM decide what they are, or impose a hurdle and take some more time to think about, like the documents being in a language none of the characters speak. She then has the time the players spend having their characters hunt up a translator in which to decide on interesting secrets to reveal. The rulebook covers a bunch of boundaries and opportunities for the narrator, with good clear examples of each.

A special kind of scene occurs when a character reaches the crisis point of having one of the three attributes’ rating get down to 0. The player may decide to play out the scene of death, madness, retreat from the world, or otherwise final fate. Or the player may think that the nature of the crisis allows for some prospect of recovery, and set up a scene in which the character begins the long road back. Characters in recovery can’t participate in conflicts for a while (though they can still comment and do things that don’t call upon the rules to resolve), then have scenes covering aspects of recovery and get the lost trait back at a reduced level.

Hidden agendas that’ve been used the number of times they’re available get resolved in special scenes, too. The player has a tally of whether each invocation of the agenda was positive or negative, and these each provide a complication. The player narrates the moment of resolution, and each of the other players gets to pitch in a complication in turn, as long as there are +s and -s to use up. Then the player gets to choose a new agenda, which may follow on the heels of the settled one – an example is having “get the love of my life to marry me” followed up by “earn the respect of her family” – or may allow the character to take a change of pace in their life’s course. One of the few real limits is that the new one has to have a different rating than the old one: a level 9 agenda must be followed by a 3 or 5 agenda, until the character’s had one of each. Then free choice resumes. It took me a moment to realize that what this does is even out characters’ pacing in long-running games. Sometimes they’re hot, sometimes cold, and it’s very unlikely that every character will have the same agenda ratings all the time. The spotlight therefore shifts smoothly without calling for much fuss on anyone’s part.

The Rest of the Book

The last seventy or so pages of the book are full of resources for the GM. There’s advice on having each stage of play run smoothly, with troubleshooting tips for common kinds of failure. There are great pieces on real landmarks like the Maunsell Forts and ideas about how they may be used in the Hot War milieu. (As usual, Malcolm provides several good ideas rather than dictating a canon.) There’s a guide to the major social and political factions in post-war Britain, the components of the Special Situations Group, and how they hate each other. There’s a really interesting guide to parts of London and environs, emphasizing dramatically suitable environments and suggesting scenes and plots that go with each. There are rules for generating simple NPCs with a roll or two, advice on making more detailed antagonists and other supporting characters, and plenty of examples of each. Likewise for the war’s horrors – which are, to my delight, described very phenomenologically, their mysteries left for each campaign to settle on their own.

There’s also a great one-page player’s primer, also available for download from Contested Ground in a link way up there somewhere. It covers both the ambience and the rules very concisely. Finally, there are blank forms for recording characters, NPCs, and the overall aims of the campaign, including its intended tone and duration, example scene photos, and so on.

The index did not fail me on anything I tried looking up in it, which is the measure of index success for me.

Verdict

Well, for starters, I wouldn’t write four thousand words about a game I didn’t care about. So it certainly passes the “is this interesting?” test.

Back in my White Wolf days, then-developer Richard Dansky told me that the real test of a book of resources for a character class or other such group is whether it made the reader think, “My life is a hollow lie if I don’t play this.” I’ve referred ever since to the hollow-lie test, and been delighted when anything I help make gets that response in reviews and comments. Hot War passes it with flying colors, for me. I really need to reassemble my playtesting group pronto, because I want to play this game so bad.

I endorse this product or service.